More Information

Submitted: April 11, 2023 | Approved: May 27, 2023 | Published: May 29, 2023

How to cite this article: Al Saadoon MA, Allouyahi MS, Almamari SA, Rizvi S. Child protection services during COVID-19 in Oman, child protection workers views. J Adv Pediatr Child Health. 2023; 6: 022-030.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.japch.1001056

Copyright License: © 2023 Al Saadoon MA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Child maltreatment; Child abuse; Child protection services; COVID-19; Social work; Oman

Child protection services during COVID-19 in Oman, child protection workers views

Muna Ahmed Al Saadoon1*, Mohammed Saif Allouyahi2, Shahad Abdullah Almamari2 and Syed Rizvi3

1Associate Professor, Child Health Department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

2Student, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

3Assistant Professor, Family Medicine and Public Health Department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

*Address for Correspondence: Muna Ahmed Al Saadoon, Associate Professor, Child Health Department, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: Child Protection Services (CPSs) are dedicated to providing protection and responding to any threats a child could face as children worldwide could be abused. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic affected all aspects of life. Procedures implemented to restrict the spread of the disease (such as reduced access to services, school closure, and social distancing measures) had an impact on child life and maltreatment. Therefore, it is important to know the impact of this pandemic on child abuse and protection.

Aim and rationales: This study aimed to assess the impact of COVID-19 on CPSs in Oman by studying the change in the number of reported cases of child abuse and the change in the reporting procedure at the Ministry of Social Development (MOSD). In addition, know the impact of the restriction measures on child rights and risk factors of child maltreatment based on CPSs workers’ opinions and experience. To understand the adaptation of the CPSs to the change in work and life environment imposed by COVID-19.

Method: A cross-section study was conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire, that was distributed to the workers involved in the CPSs at the MOSD in Oman. Data also were collected from the statistical bulletins on the Ministry’s website.

Results: COVID-19 pandemic was not found associated with a significant change in the number and type of child abuse cases reported to the MOSD. The reporting procedures also did not change. In addition, the pattern of child abuse types did not change before and during the pandemic, as neglect cases were the most. The participants judged the restriction measures affecting family life through separation, cyber abuse, and reduced educational support. With regard to intervention and follow-up procedures, the main difference was in the communication processes by using online communication methods and reducing the fieldwork for mild cases.

Conclusion: CPSs in Oman were not much affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which may reflect the success of this system in dealing with the restriction measures. However, more solutions should be developed to adapt to these circumstances in the future altogether.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic started in December 2019 in Wuhan. In Oman, the first two cases of COVID-19 were reported on the 24th of February, 2020 [1]. Protective measures such as social distancing, travel restrictions, isolation, and closure of institutions were taken by governments to control the spread of the virus. These measures affected life aspects, including economic, social, educational, and health. The restriction of movement also contributed to the reduction of access to education and health services [2,3].

The American Academy of Pediatrics estimated that more than one billion children are abused every year [4,5]. Child maltreatment can cause many problems for the child especially mental problems and poor development in many domains such as language, cognitive, neurobiological, and socioemotional [6]. Child maltreatment increased during COVID-19 with associated limited access to services as schools and other resources were closed [7]. The effect of this pandemic was directly seen in the decrease in the care that the family provides to their children because of decreasing in their capacities, socioeconomic stress, and the closing of essential services and schools [2,9-10].

There is also an increase in the exploitation of children who have lost their parents due to the virus, such as sexual exploitation of girls, early marriage of girls, and illegal work [10]. Evidence showed that parents are among the perpetrators during the pandemic in relation to family instability in such circumstances [11]. These impacts were more in lower-income communities compared to higher-income communities [12].

Child Protection Services (CPSs) are essential to respond to any threats a child could face [6]. Laws, regulations, and protection systems have been established in Oman to ensure that child’s rights are kept, to prevent abuse, and to identify and manage victims of child maltreatment [13]. However, studies showed that reporting and calls received by CPSs decreased during the pandemic [7,14]. Countries noted that it was necessary to find alternative methods to receive the reports, such as Child helplines, easily accessible smartphone applications and enabling reporting via some centers that were not closed during the spread of the pandemic, such as pharmacies and supermarkets [7]. Australia, Canada, and Germany considered CPSs to be among the necessary services that should not be closed under the influence of protective measures against COVID-19 [3]. The lockdown and isolation measures did affect also the social workers and the professionals who work in the CPSs. Hence, they had to adapt to the situation and continue providing the necessary protection to children while maintaining COVID-19 prevention measures. In a survey conducted in England and Wales, the social workers and professionals in the CPSs system showed a great adaptation in the change in their work from the original methods to online methods as most of their work was done online by video or by a telephone conference [15].

Like other countries, there have been cases of children being exposed to violence in Oman. According to MOSD published data, there were 102 cases of child abuse in 2015, and 54% of these cases were males. The majority of the cases were cases of neglect (56.9%), followed by physical abuse (23.5%), and then sexual abuse (18.6%). Oman’s interest in child protection appeared a long time ago and was internationally observed when the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was ratified in 1996 [16]. Later, child protection committees were established, and 11 multi-disciplinary child protection working teams in 2008. In 2016, the child protection Hotline was developed to provide a better reporting facility [13].

This study aims to assess the impact of COVID-19 on CPSs in Oman by studying the change in the number of reported child abuse cases, the change in procedures of reporting, intervention, and follow-up, and the effect of restriction measures on child rights.

This study is a cross-sectional study evaluating the CPSs provision during the COVID-19 duration from 2020-2021. The target group was all workers in the child protection field at the MOSD in Oman (55 workers involved in CPSs at the MOSD). They included social workers, child protection delegates, psychologists, family counsellors, guidance specialists, and others. Basic data about reported child abuse cases before and during the pandemic and statistics according to the type of abuse were collected from the MOSD’s website.

Study tool

The data was collected through a questionnaire developed by the research team based on study objectives and literature review. The questionnaire contains five sections: the demographic characteristics. the child rights and risk factors of child abuse and neglect which include: stigmatization, family separation and divorce, unpaid care and domestic work, abuse of orphaned children, and educational support. The reporting of suspected cases was the third section which include: the opinion about the change in the type, number, and severity of reported cases. The change in the rate of cyber abuse and procedure of reporting child abuse, changes in the number of cases reported by the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Health. The fourth section was about the intervention (management, referrals, and follow-up) which include: the ability to communicate with family and children during the pandemic, changes in the procedure of follow-up and referral cases, ways used to communicate with children and their families during the pandemic, opinions of social workers in process of adaptation in intervention, challenges, and recommendations. There are a few open-ended questions in the fourth and fifth parts of the questionnaire, which provide qualitative information regarding the study. The content and face validity of the tool were checked by ten experts in child protection social work and questionnaire-based studies. Modifications based on the experts’ notes and suggestions were made to come up with draft one of the study tool. A pilot study of the tool was conducted on 8 social workers from different institutions (excluding MOSD) and their feedback was used for the second revision of the questionnaire.

Data collection

The questionnaire (hard copies and Google form) was distributed during November-October 2021 to workers involved in child protection services at the MOSD in Oman after obtaining their consent to participate in the study. Statistics of child abuse cases that were reported to the MOSD in Oman (from 2018 to 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, and from 2020 to 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic) were collected from the statistical bulletins on the Ministry’s website and verified with the MOSD.

Data analysis

The changes in reporting procedure and the factors of child abuse in CPSs were described by frequencies, percentages, and descriptive statistics using the Statistical Package of the Social Science (SPSS) software (version 23.0). The categorized variables were also described and presented with appropriate graphs and tables to display the research findings. The qualitative data was analysed using an interpretative phenomenological approach, with the aim of understanding individuals’ perceptions of a particular experience.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC#2495), College of Medicine and Health Sciences, at Sultan Qaboos University and permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the MOSD.

Out of the 55 MOSD staff working in the child protection services, thirty-three participated in the study with a response rate of 60%. Table 1 displays the distribution of various demographic characteristics of the studied group. Two-thirds of the respondents (66.7%) were females. The majority of the respondents were aged between 31 to 40 years (63.6%). As per the literacy status of the studied group; most of them (84.8%) were graduates or above.

| Table 1: Demographic characteristics. | |||

| Demographic characteristics | Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Sex | Male | 11 | 33.3 |

| Female | 22 | 66.7 | |

| Age | 20-30 | 3 | 9.1 |

| 31-40 | 21 | 63.6 | |

| 41-50 | 7 | 21.2 | |

| >50 | 2 | 6.1 | |

| Qualification | Diploma degree | 5 | 15.2 |

| Bachelor's degree | 20 | 60.6 | |

| Master's degree | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Ph.D. degree | 1 | 3 | |

| Job | Family counseling and guidance specialist | 5 | 15.2 |

| Social worker | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Psychologist | 5 | 15.2 | |

| Child protection delegates | 4 | 12.1 | |

| Administrative jobs | 9 | 27.3 | |

| Others | 3 | 9.1 | |

| Number of years of experience | 1-5 | 2 | 6.1 |

| 6-10 | 21 | 63.6 | |

| >=11 | 10 | 30.3 | |

| Nature of work | Fieldwork | 2 | 6.1 |

| Office work | 5 | 15.2 | |

| Both | 26 | 78.8 | |

| Nationality | Omani | 33 | 100 |

| Non-Omani | 0 | 0 | |

| Governorate | Muscat | 11 | 33.3 |

| Ash Sharqiyah | 7 | 21.2 | |

| Ad Dakhiliyah | 6 | 18.2 | |

| Dhofar | 5 | 15.2 | |

| Al Batinah | 4 | 12.1 | |

The reported child abuse cases to the MOSD during the years (2018-2021)

The statistics of cases reported to MOSD during 2018-2021 Table 2 shows the numbers of cases reported through the child helpline during each quarter of each year and reports from other sources. The period from 2018 to 2019 was considered pre-COVID-19, while 2020-2021 has been taken as the COVID-19 period. The total number of reports before the pandemic (2018-2019) was 2629, while there were 2690 reports during the pandemic (2020-2021), indicating not much change in the total number of reports. There were 1469 reports from the child helpline before the pandemic (2018-2019) and 1313 reports during the pandemic (2020-2021). However, the number of reports from sources other than the child helpline (such as notifications from schools and health institutions) was low at the beginning of the pandemic (during 2020), while there was a marked increase in reports from other resources in 2021.

| Table 2: Numbers of reported cases from 2018-2021 at the Ministry of Social Development (MOSD). | |||||||

| Year | Numbers of Reported Cases | Total | |||||

| Child Helpline (CH) | Other Sources | ||||||

| First Quarter | Second Quarter | Third Quarter | Fourth Quarter | Total (CH) | |||

| 2018 | 168 | 177 | 225 | 109 | 679 | 601 | 1280 |

| 2019 | 188 | 142 | 195 | 265 | 790 | 559 | 1349 |

| 2020 | 169 | 109 | 151 | 178 | 607 | 433 | 1040 |

| 2021 | 165 | 158 | 176 | 706 | 944 | 1650 | |

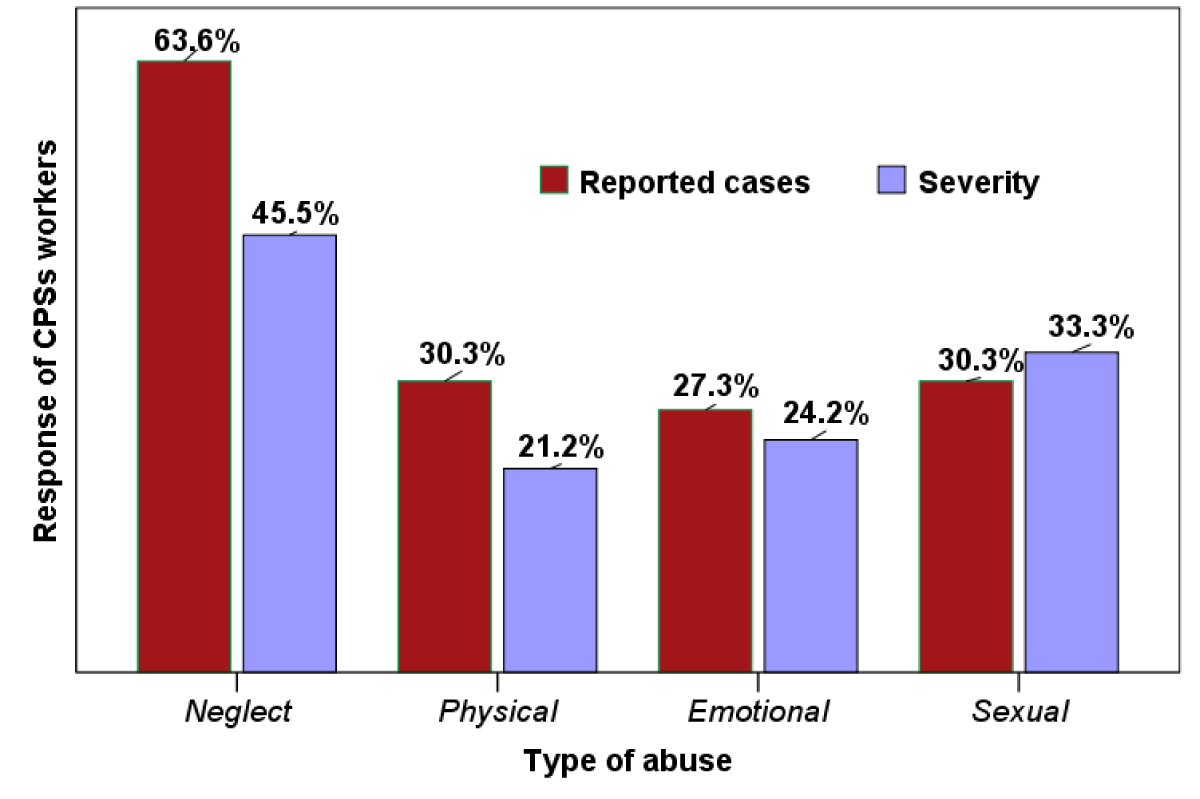

Child abuse types pattern and reporting of child abuse from other institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic Figure 1 represents the types of child abuse that children are exposed to according to the experience of CPSs workers. Neglect cases were the most frequent along with the severity during the COVID-19 period, as agreed by 63.6% and 45.5% of the workers, respectively. On the other hand, emotional abuse cases were the least frequent (27.3%) and physical abuse was the least severe (21.2%) as per the opinion of the participants.

Figure 1: Opinion of CPSs workers about the increase in reported cases of child abuse and their severity during the COVID-19 pandemic

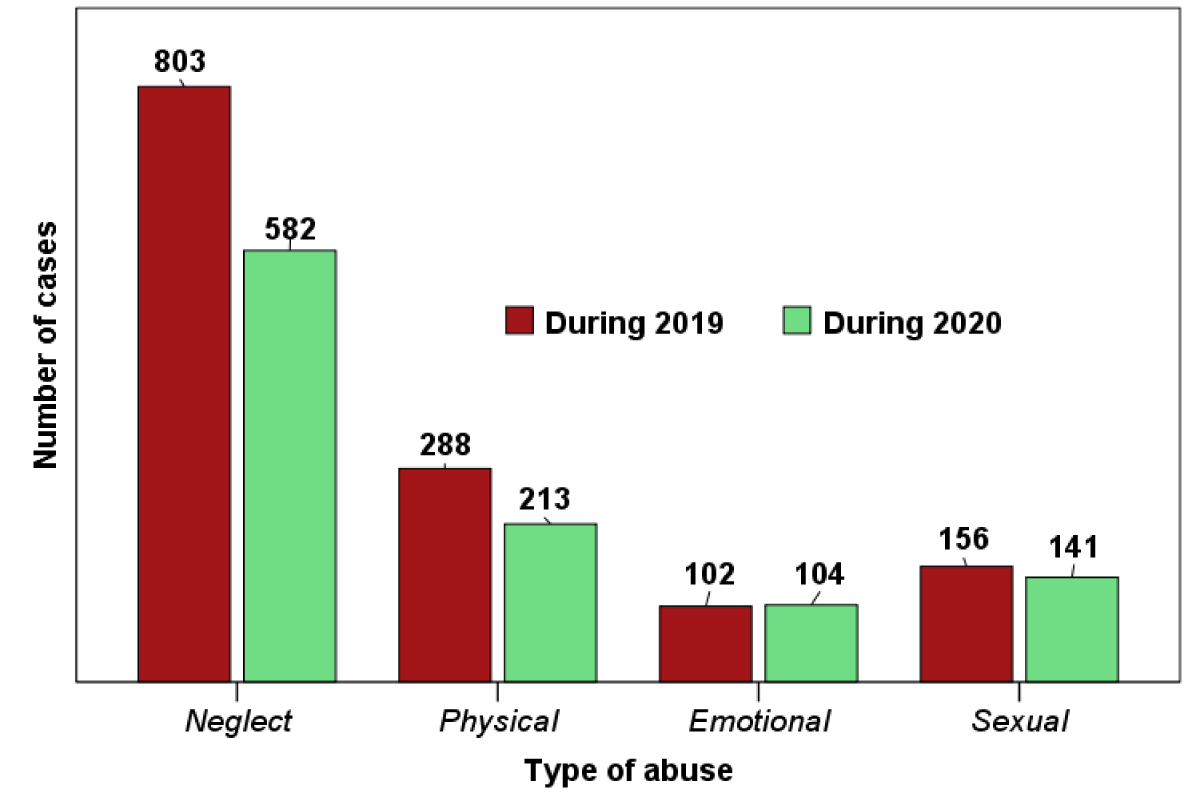

Figure 2 shows the actual number of cases reported for each type of abuse before (2019) and during (2020) the COVID-19 pandemic to the MOSD. It is clear that neglect cases were, and still, are the most, regardless of the impact of the restriction measures of COVID-19, as well as emotional abuse cases, which were the least.

Figure 2: Actual numbers of reported cases at the MOSD during 2019 and 2020.

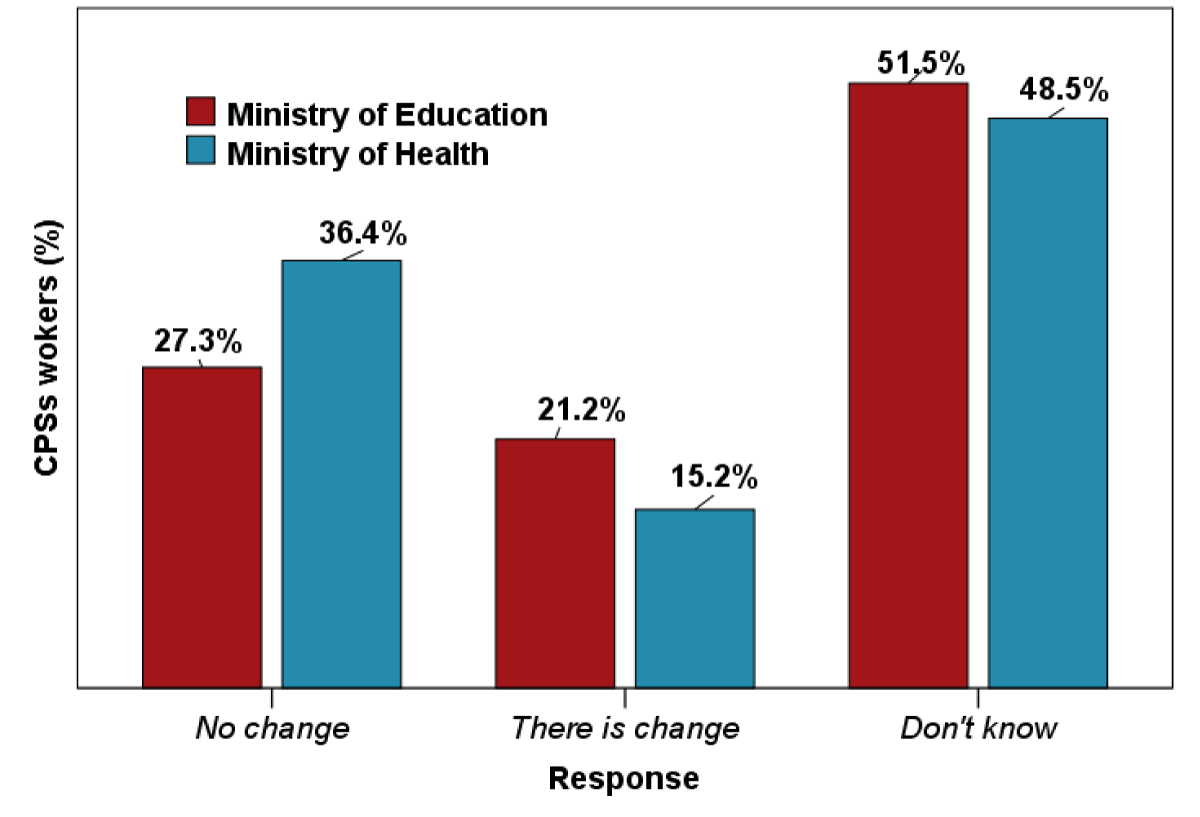

Some of the participants reported that there was a change in the number of cases reported by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ministry of Health (MOH). They reported that there was a decrease in the reporting from the MOE and an increase in reporting from the MOH. They also noted the rise in neglect and sexual abuse cases reported by these two ministries. About half of the respondents didn’t give their opinion regarding the change in reporting from the two ministries. Figure 3 displays the opinion of the CPSs employees regarding the change in reporting.

Figure 3: Opinion of CPSs workers about the change in the number of cases reported by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ministry of Health (MOH) during the COVID-19 pandemic..

Changes in the reporting procedure

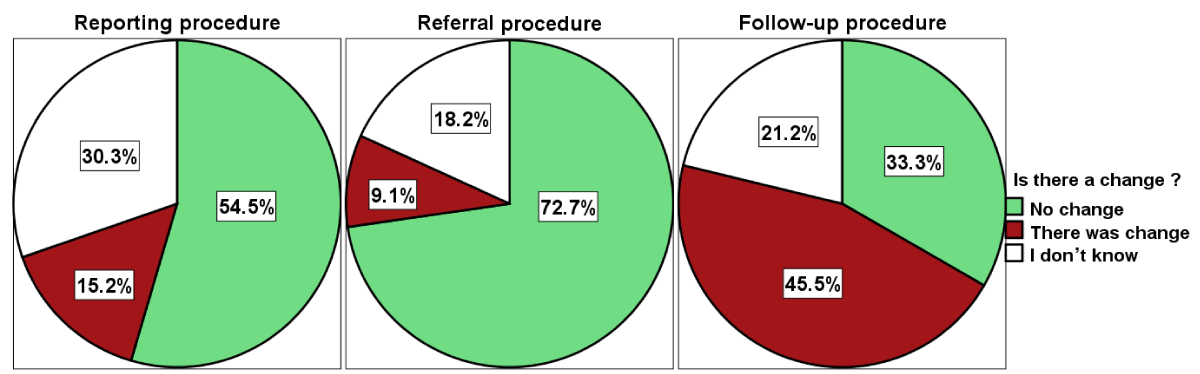

According to the statistics from Table 2, most of the reports before and during the COVID-19 pandemic reach the MOSD through the child helpline. More than half of the participants (54.5%) agreed that there was no change in the reporting procedures, Figure 4. Those who answered that there was a change (15.2%), stated that the electronic methods to receive child abuse notifications had been introduced, in addition to receiving reports according to the type and severity of cases to prioritize cases for home visits arrangement for severe cases.

Figure 4: Opinion of CPSs workers about the change in the reporting procedures during the pandemic.

Child rights and risk factors of child abuse

Table 3 shows the CPSs workers’ opinions based on their experience in child protection services during the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in the tables, 36.4% think there was a mild increase in family separation or divorce during the COVID-19 pandemic, while 21.2% said there was no change. More than half of the workers (51.5%) were not aware if there was a change in the orphanhood rate during the pandemic. Those who thought that there was an increase (Mild increase (24.2%) and major increase (15.2%)) were asked whether there was an increase in the abuse of orphaned children, and 72.7% of them answered there was not. In addition, 42.4% of participants agreed that there was no increase in children’s unpaid care and domestic work during the COVID-19 pandemic, and only 27.3% stated that there was an increase Table 3.

| Table 1: Opinion of CPSs workers on the change in the demographic factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||||||

| Factor | No change | Decrease | Increase | Don’t know | ||

| Mild | Major | Mild | Major | |||

| Orphan hood rate | 9.1% | -- | -- | 24.2% | 15.2% | 51.5% |

| Unpaid care and domestic work | 42.4% | -- | -- | 18.2% | 9.1% | 30.3% |

| Educational support | 3.0% | 36.4% | 45.5% | -- | -- | 15.2% |

| Family separation/divorce | 21.2% | 3.0% | 36.4% | 6.1% | 33.3% | |

On the other hand, 45.5% of the workers reported that there was a major decrease and 36.4% reported a mild decrease in educational support for the children during the pandemic Table 3. There was also a question about the change in the rate of cyber abuse of children during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 76.8% of participants replied that there was an increase in cyber abuse cases. And when asked about stigmatization and discrimination against children affected by Coronavirus, 66.7% replied that there was no such issue.

Intervention and referral procedures

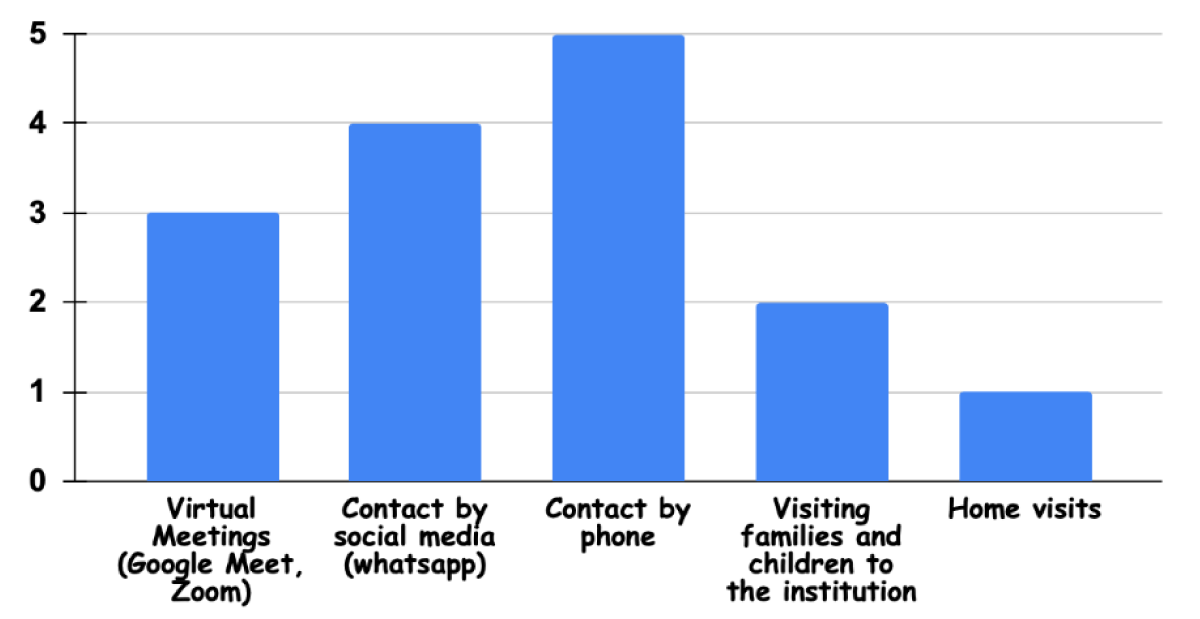

Figure 5 presents the most common communication methods with children and their families to provide interventional services during COVID-19. Contact by phone, contact by social media (WhatsApp, for example), and virtual meetings such as Google Meet and Zoom were the more frequently used methods. The least used ways were visiting the institution and home visits.

Figure 5: Modes of communication to provide intervention for child protection cases during COVID-19.

The participants stated the ways for assisting the change in the intervention procedures, which can be listed as follows:

- Direct call and call for office attendance: There is a formal communication process between the MOSD and the families to organize the visiting process during the pandemic period and avoid crowding in the institution.

- Follow-up on the phone: this communication method appeared during the pandemic, and it was used for mild cases that did not need urgent intervention.

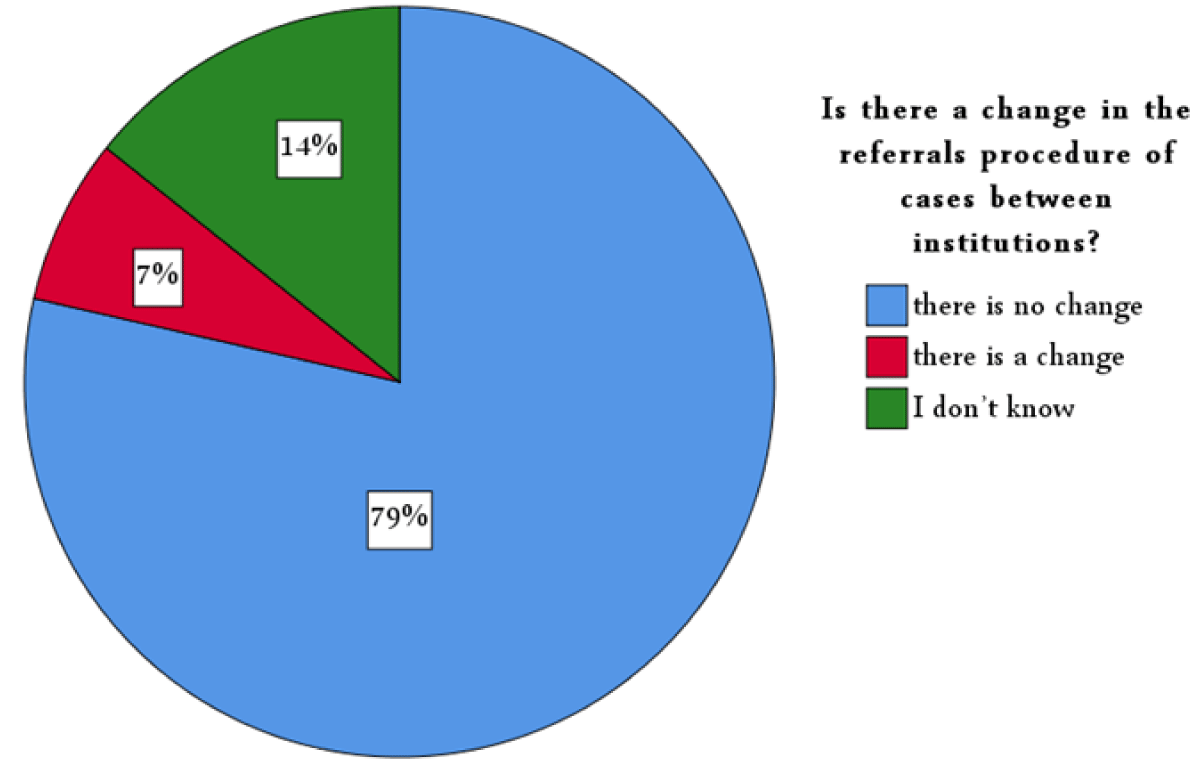

The referral procedures: Most of the participants (79%) agreed that there was no change in the referral procedures between institutions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, among those who stated that there was a change, they stated that the difference was by introducing a new form to receive notifications and communicating with the Ministries to facilitate the procedures and to assure early appointments (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The change in the referral procedures of cases between institutions.

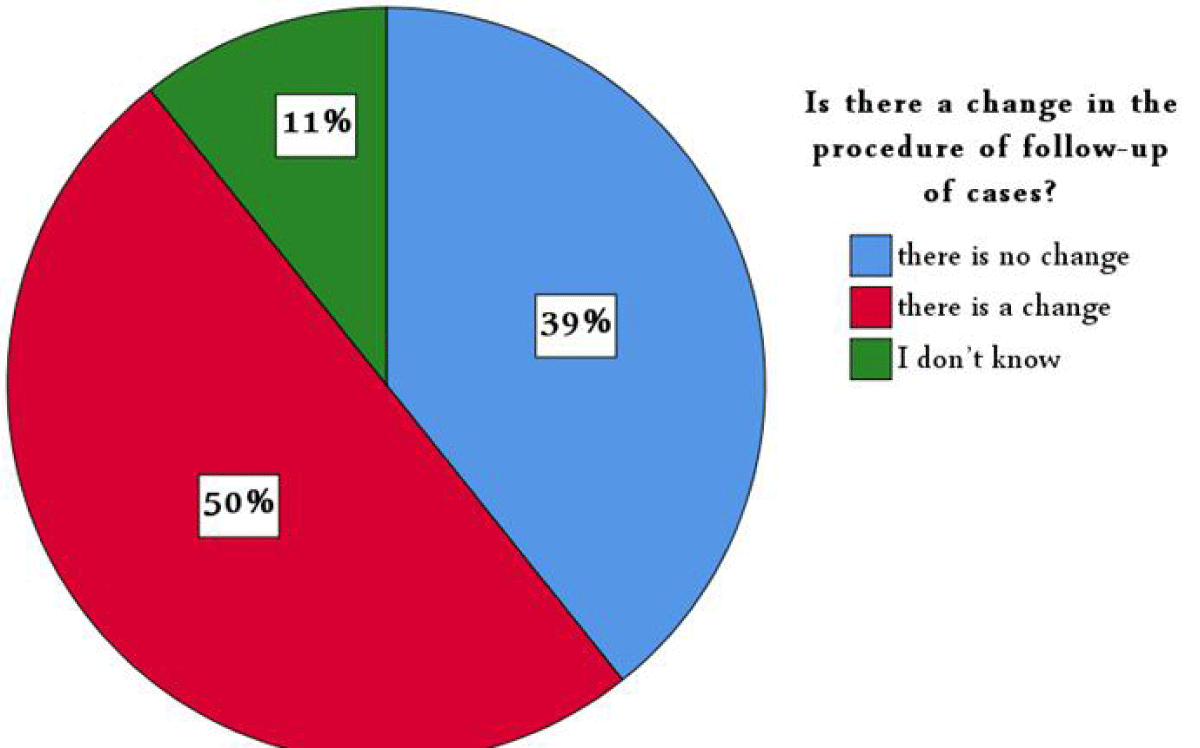

Follow-up procedure: Half of the participants thought there was a change in the follow-up procedures for child maltreatment cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on Figure 7, 50% of the participants stated a difference in the follow-up procedures, and 39% believed there is no change in the follow-up process. 11% of participants said they did not know if there was a change.

Figure 7: Bio-faithful AD caseThe change in the procedures of follow-up of the cases of child maltreatment..

Participants stated the following three main changes:

- Reduced fieldwork: especially during the lockdown at the peak of the pandemic. The fieldwork significantly declined, and it was only restricted to the maltreatment cases that need a direct/urgent follow-up.

- Increased online communication: using phones and social media, especially phone calls and video calls.

- Case Severity classification guided decisions: They were dealing with urgent and severe maltreatment cases through the home or institution visits. While mild non-urgent cases were followed up remotely using phone or online communication.

Child protection serveries challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic

The challenges reported by the participants were categorized into four groups by the analysis: procedures:

- Field-related challenges: including difficulties in movement due to emergency lockdown and social restriction procedures of COVID-19.

- Technical challenges: include poor networks and network interruptions, lack of appropriate devices, and lack of internet service for some families.

- Cultural challenges: including the reluctance of some families to provide the electronic device and the lack of support available from this aspect.

- Health challenges: include the inability to have face-to-face contact with some children, which could negatively affect the quality of services provided to them.

Although most participants state some challenges, few participants state that there were no challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 4 shows the participant’s recommendations for improving the CPSs in Oman during similar situations in the future.

| Table 4: The participant's recommendation for improving child protection services. | ||

| Technical: improving the technical support or providing technical equipment | By providing special rooms equipped with modern technologies for remote communication with children, training specialists on using them, especially the technical aspect, and providing them with electronic devices. | |

| Material: increasing the building capacity | Increasing the space and providing financial support. | |

| Training and staff development | For workers on child protection. | By working on finding and developing alternative work mechanisms by developing well-thought-out plans that can be implemented during an emergency that helps workers to facilitate the exercise of their work tasks, forming a dedicated team with precautions, and training staff on the basics of dealing with emergencies, especially regarding the difficulty of reaching the beneficiary group, including children. |

| For the families. | By conducting training programs for families, training families in using the means of Communication and electronic programs for interviews to reduce field visits that may cause an increase in infection during the pandemic. | |

| Collaboration between different sectors | It is necessary to link all institutions and sectors and prepare employees to use modern technologies. By establishing electronic communication channels and electronic data systems that link the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education with the MOSD. | |

This is the first study on the impact of COVID-19 on Child Protection Services (CPSs) in Oman, which focus on the effect of the pandemic on reporting, intervention, follow-up procedures of child protection services, and the risk factors of child abuse. This study detected no significant change in the total number of reported child abuse cases to the MOSD during the pandemic duration (2629 reports before the pandemic and 2690 reports during the pandemic). In Oman, reporting child abuse through the child hotline was active throughout the pandemic duration, which might explain this finding. This is similar to a study that reported that children being assessed for suspected physical abuse during 2020/2021 were in line with the preceding 4 years [17]. But contrary to other studies that reported a decrease in reports during the COVID-19 period [11,18]. A possible reason for this decline in reporting is reduced access to the services (among which reporting service) in the presence of the restriction measures. Studies also found the number of children subject to Inter-Agency Referral Discussion fell but a higher number of children were placed on the Child Protection Register during restrictions [19]. These findings should be interpreted cautiously as studies indicate that family violence increase in emergencies yet reporting of violence is suppressed due to disruption in reporting mechanisms and infrastructure [20-24].

However, this study result showed a decrease in the number of reports from other sources (such as notifications from schools and health institutions) at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (607 reports from the child helpline and 433 reports from other sources during 2020). This is similar to a study in Colombia, which compared 2019 and 2020 reports, and the result showed a significant drop (78%) in reporting by attending to the institution, while there was a 23% increase in telephone reports [3]. This may reflect the success of the countries in increasing the utilization of reporting services that are appropriate to the restriction protection measures.

The participants’ opinions indicate neglect cases were the most frequent and severe cases during the pandemic, while physical abuse cases were the least. This pattern is similar to the reported abuse types before the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, there were no changes in the pattern of types of child abuse in Oman during this pandemic. This was in agreement with a study in the United States that showed that neglect cases were the most, even with a marked drop in reports. However, the sexual abuse cases were the least [11]. Studies suggest that the increase in abuse and neglect may be due to family isolation, separation, or weakness of the parents and caregivers due to illnesses or other stresses due to the pandemic [25]. Therefore, it is essential to support families and caregivers of children and ensure the stability of the family to prevent this type of abuse during similar crises.

This research also studied the change in the number of cases reported by the MOE and the MOH during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings according to the workers’ knowledge of the notifications received from these two ministries showed a slight decrease in the reporting of child abuse from the MOE. A study from the United States; Florida, showed that the levels of reporting decreased by 27% from schools after applying the restriction measures [11]. Another study that compared 2019 and 2020 reports showed 25.59% of reports came from schools in 2019 and only 13.42% in 2020 [12]. This could be explained by the fact that most countries (among which Oman) closed schools during the pandemic and implemented the distance learning system. Hence, direct contact with students in the schools decreased with possibly fewer chances to recognize abuse. On the other hand, the participants agreed that there was a slight increase in child abuse cases reported from the MOH similar to other studies observation of increase in receiving reports from different sectors like the health sector [12].

The change in the reporting procedures at the MOSD in Oman based on the CPSs workers’ opinion was unnoticeable. More than half of the participants (54.5%) agreed that there was no change in the reporting methods. UNICEF reported new ways of receiving reports of child abuse applied by some countries to adapt to COVID-19 restriction measures, such as child helplines, smartphone applications and enabling reporting via some centres that were not closed during the spread of the pandemic, like pharmacies and supermarkets [7]. These differences between the reporting procedures in this study and other countries may reflect the efficacy of the reporting system with the existing child helpline in Oman. The current study reported a few changes in the way of receiving reports, such as receiving reports according to the type and severity of cases to prioritize cases for home visits arrangement for severe cases. In addition, electronic methods to receive child abuse notifications had been introduced.

From this study, the change in the intervention and referral procedures showed increased online technical communication via phone and social media, which is similar to other research findings. Research conducted in 2020 in England studied the initial effect of the lockdown and COVID-19 restrictions on child protection. The result points to the replacement of personal visits with virtual visits. However, workers were worried about this transformation as they were concerned about their ability to build meaningful relationships with the children and complete, accurate assessments of the family and child [26,27].

This study showed no change in the referral procedures as most of the cases are managed by the professionals within the MOSD. For others that needed referral, the existing referral system to other institutions was adequate (phones, faxes, emails). Some participants recommended increasing the collaboration between the institutions for better and fast services. Other studies had similar findings, as only referrals of cases that are judged to be at great risk during the online communication assessment and evaluation are visited by the workers using personal protective equipment, and social distancing measures were possible [26].

50% of the participants in this study reported a change in follow-up procedures, like a study done in England. Plenty of their participants agreed that there was a change in the follow-up procedures of the CPSs during COVID-19 [15]. The difference in the follow-up procedures in this study was in reducing filed work, depending more on online communication methods, and categorizing the cases according to severity so that prioritization of home visits could be done. Other studies showed a shift to virtual home visiting rather than personal visiting, and more use of remote communication such as text messaging [15]. Such an approach was necessary during the pandemic and helped to provide intervention to requiring families, but challenges were experienced by families and workers [28].

Lockdown and restriction measures because of COVID-19 can affect child rights and the risk factors of child abuse. This research studied the change in some factors, including family separation, cyber abuse, educational support, orphaned abuse, unpaid care and domestic work, and stigmatization and discrimination. According to the participants’ opinions and their experience in the child protection field, there is a mild increase in family separation during the pandemic, as agreed by 36.4% of participants. This separation may include divorce, and isolation due to the pandemic among other causes. Such separation may negatively affect children as they might lose the attention and care of their parents. Furthermore, participants reported an increase in cyber abuse cases (as agreed by 76.8% of the participants). This is similar to the U-Report (2020) international survey, which found that 47% of participants who were under 19 reported cyber abuse such as cyberbullying, harassment, and hate speech [3]. This factor is very important and should shed light on it, as the world is currently going towards online services in every aspect of life. As a result, children’s usage of the Internet for the purpose of study and contact has increased, and lack of supervision and protection may lead to their exposure to cyber abuse.

Educational support is one of the child’s rights, and participants replied that there was a decrease in educational support during the pandemic. Schools closed causing the inability of some families due to the economic state to enhance online educational services. The negative impact of COVID-19 on educational support was also observed in other studies [12]. Therefore, this decrease could lead to an increase in child maltreatment cases and less identification and reporting for appropriate intervention, and a major impact on academic performance.

The participants agreed that there was no change in the orphaned abuse rate, unpaid care and domestic work, and stigmatization and discrimination of children. Although the participants agreed that there was an increase in the orphanhood rate due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 72.7% of the participants emphasized that there was no increase in abuse of those orphaned children. This is inconsistent with a review of the impacts of pandemics and epidemics on child protection, which found that being orphaned is a direct outcome of these circumstances, and children become at risk of abuse, especially sexual exploitation of girls and child laborers of boys [10]. This result of no increase in abuse of orphaned children could be explained by continued attention and care for them by the extended family during the restriction measures period in Oman and the support by MOSD.

In addition, the result also showed no change in the unpaid care and domestic work of children, which is the services provided by the person for the family members within a house, and it is considered a type of child labour [29]. This could be explained by the support that families received from the government, community societies, and extended family. On the contrary, UNICEF reported increasing unpaid care and domestic work during the spread of pandemics and epidemics [10].

The last factor is stigmatization and discrimination against children affected by Coronavirus, and 66.7% of participants agreed that there was no concern about this. Contrary to a systematic review, they found that stigmatization and discrimination are widespread social phenomenon for those with infectious diseases, mostly by their peers and teachers [30,31].

Improvement of the CPSs during COVID-19 can be achieved by studying the limitations and eliminating them, looking at the best practices, and trying to implement them. The participants pointed out some challenges and the most significant were technical: issues with technical knowledge and materials and field challenges that can be overcome by improving technical support or providing technical equipment and training to staff so they can perform child protection tasks in a better way during similar situations in the future. Studies mentioned that lack of internet and technical support is a significant limitation that can be eliminated by improving the network and training the workers and families as well on how to use technical equipment [26].

The COVID-19 pandemic was not associated with major changes in child abuse reports to MOSD. However, reporting from the MOE was decreased due to school closure. The CPSs were affected as there was a change in the intervention procedures and communication methods between the workers with the child and families. There was more use of online communication techniques such as contact via phones and social media. This was also applicable to the follow-up procedures replacing home visits. This study has to be interpreted with caution due to its limitations. The small sample size that limited advanced statistical analysis added to the self-completed questionnaire-based study limitations. Generalization of the results is not possible as the response from some governorates was low. Finally, as it is a cross-sectional study, temporality cannot be established, and causality can be very difficult because of the lack of temporality.

Recommendations

To improve the work of the CPSs, especially during emergency situations the concerned institutions should consider the following recommendations:

- Provide adequate technical support and training to members of the child protection services. This would maximize the benefit of the utilization of remote service provision.

- Improvement of resources: improving physical space that could provide a comforting and safe environment for children, families, and workers. This includes also equipping the institutions with technical equipment and softwares for online data storage/share, and optimum remote services.

More studies about the impact of COVID-19 on CPSs are needed to support the findings of this study. Expanding the targeted group to include other Ministries, such as MOE and MOH is highly recommended to get more data about challenges, limitations, and the required changes in the process of the CPSs in Oman to improve it.

We would like to thank the social workers for their participation in this study and the Ministry of Social Development staff for their cooperation.

- Al-Mahruqi S, Al-Wahaibi A, Khan AL, Al-Jardani A, Asaf S, Alkindi H, Al-Kharusi S, Al-Rawahi AN, Al-Rawahi A, Al-Salmani M, Al-Shukri I, Al-Busaidi A, Al-Abri SS, Al-Harrasi A. Molecular epidemiology of COVID-19 in Oman: A molecular and surveillance study for the early transmission of COVID-19 in the country. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Mar;104:139-149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.049. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33359061; PMCID: PMC7834852.

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020 Jun;78:185-193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. Epub 2020 Apr 17. PMID: 32305533; PMCID: PMC7162753.

- Katz I, Katz C, Andresen S, Bérubé A, Collin-Vezina D, Fallon B, Fouché A, Haffejee S, Masrawa N, Muñoz P, Priolo Filho SR, Tarabulsy G, Truter E, Varela N, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment reports and Child Protection Service responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa. Child Abuse Negl. 2021 Jun;116(Pt 2):105078. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105078. Epub 2021 Apr 28. PMID: 33931238; PMCID: PMC8446926.

- Hillis S, Mercy J, Amobi A, Kress H. Global Prevalence of Past-year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates. Pediatrics. 2016 Mar;137(3):e20154079. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4079. Epub 2016 Jan 25. PMID: 26810785; PMCID: PMC6496958.

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011 May;16(2):79-101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. Epub 2011 Apr 21. PMID: 21511741.

- Charles H. Zeanah, Kathryn L. Humphreys. Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018; 57 (9): 637-644,

- Bhatia A, Fabbri C, Cerna-Turoff I, Tanton C, Knight L, Turner E, Lokot M, Lees S, Cislaghi B, Peterman A, Guedes A, Devries K. COVID-19 response measures and violence against children. Bull World Health Organ. 2020 Sep 1;98(9):583-583A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.263467. PMID: 33012855; PMCID: PMC7463187.

- Baron EJ, Goldstein EG, Wallace CT. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. J Public Econ. 2020 Oct;190:104258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258. Epub 2020 Aug 21. PMID: 32863462; PMCID: PMC7441889.

- Hurt S, Ball A, Wedell K. Children more at risk for abuse and neglect amid coronavirus pandemic, experts say. USA Today. 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/ investigations/2020/03/21/coronavirus-pandemic-could-becomechild-abuse-pandemic-experts-warn/2892923001/

- Bakrania S, Chavez C, Ipince A, Rocca M, Oliver S, Stansfield C, Subrahmanian R. Impacts of Pandemics and Epidemics on Child Protection: Lessons learned from a rapid review in the context of COVID-19, Innocenti Working Paper. July 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106509%0Ahttps://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0747563220302612.

- Brown SM, Orsi R, Chen PCB, Everson CL, Fluke J. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Protection System Referrals and Responses in Colorado, USA. Child Maltreat. 2022 Feb;27(1):3-11. doi: 10.1177/10775595211012476. Epub 2021 Apr 26. PMID: 33896229; PMCID: PMC9011917.

- Metcalf S, Marlow JA, Rood CJ, Hilado MA, DeRidder CA, Quas JA. Identification and Incidence of Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol Public Policy Law. 2022 May;28(2):267-279. doi: 10.1037/law0000352. Epub 2022 Mar 21. PMID: 37206908; PMCID: PMC10195111.

- Al Saadoon M, Al Numani A, Saleheen H, Almuneef M, Al-Eissa M. Child Maltreatment Prevention Readiness Assessment in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2020 Feb;20(1):e37-e44. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2020.20.01.006. Epub 2020 Mar 9. PMID: 32190368; PMCID: PMC7065698.

- Martins-Filho PR, Damascena NP, Lage RC, Sposato KB. Decrease in child abuse notifications during COVID-19 outbreak: A reason for worry or celebration? J Paediatr Child Health. 2020 Dec;56(12):1980-1981. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15213. Epub 2020 Oct 4. PMID: 33012011; PMCID: PMC7675527.

- Baginsky M, Eyre J. Roe A. Child protection conference practice during Covid-19: reflections and experiences. 2020; 55. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/140253694/Baginsky_et_al_2020_Child_protection_conference_practice_during_COVID_19_report.pdf.

- Nations U. 56a1Edf94, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2015; 01185(January). https://www.refworld.org/docid/56a1edf94.html.

- McDonnell C, Courtney M, Barrett M, McDonnell T, Persaud T, Twomey E, Harty S, Byrne AT. Impact on the incidence of suspected physical abuse in children under 24 months of age during a global pandemic: A multi-centre Irish regional retrospective cross-sectional analysis. Br J Radiol. 2022 Sep 1;95(1137):20220024. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220024. Epub 2022 Jul 15. PMID: 35786972.

- Shusterman GR, Fluke JD, Nunez JJ, Fettig NB, Kebede BK. Child maltreatment reporting during the initial weeks of COVID-19 in the US: Findings from NCANDS. Child Abuse Negl. 2022 Dec;134:105929. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105929. Epub 2022 Oct 13. PMID: 36270070; PMCID: PMC9556910.

- McTier A, Soraghan J. The Utility of Administrative Data in Understanding the COVID-19 Pandemic's Impact on Child Maltreatment: Learning From the Scotland Experience. Child Maltreat. 2022 Jun 14:10775595221108661. doi: 10.1177/10775595221108661. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35702015; PMCID: PMC9204123.

- Curtis T, Miller BC, Berry EH. Changes in reports and incidence of child abuse following natural disasters. Child Abuse Negl. 2000 Sep;24(9):1151-62. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00176-9. PMID: 11057702.

- Baron EJ, Goldstein EG, Wallace CT. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. J Public Econ. 2020 Oct;190:104258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258. Epub 2020 Aug 21. PMID: 32863462; PMCID: PMC7441889.

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Cobetto C, Gandarilla Ocampo M. Child abuse prevention month in the context of COVID-19. Center for Innovation in Child Maltreatment Policy Research and Training. 2021. https://cicm.wustl.edu/child-abuse-prevention-month-in-the-context-of-covid-19/

- Seddighi H, Salmani I, Javadi MH, Seddighi S. Child Abuse in Natural Disasters and Conflicts: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021 Jan;22(1):176-185. doi: 10.1177/1524838019835973. Epub 2019 Mar 13. PMID: 30866745.

- Weiner D, Heaton L, Stiehl M, Chor B, Kim K, Heisler K, Foltz R, Farrell A. Chapin Hall issue brief: COVID-19 and child welfare: Using data to understand trends in maltreatment and response. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. 2020. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/Covid-and-ChildWelfare-brief.pdf

- Fogarty A, Jones A, Evans K, O'Brien J, Giallo R. The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic for families of infants involved with Child Protection Services for maltreatment concerns. Health Soc Care Community. 2022 Sep;30(5):1754-1762. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13555. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34435399; PMCID: PMC8653246.

- Cook LL, Zschomler D. Virtual Home Visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Social Workers’ Perspectives, Practice. Routledge. 2020; 32(5): 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2020.1836142.

- Seay KD, McRell AS. Child Welfare Services Response to COVID-19: Addressing Face-to-Face Contacts. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;30(8):2055-2067. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-02000-7. Epub 2021 Jun 16. PMID: 34155430; PMCID: PMC8208611.

- Self-Brown S, Reuben K, Perry EW, Bullinger LR, Osborne MC, Bielecki J, Whitaker D. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Delivery of an Evidence-Based Child Maltreatment Prevention Program: Understanding the Perspectives of SafeCare® Providers. J Fam Violence. 2022;37(5):825-835. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00217-6. Epub 2020 Nov 5. PMID: 33173254; PMCID: PMC7644279.

- Ferrant G, Pesando LM, Nowacka K. Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes, OECD Development Centre. December 2014; 12.

- Kimera E, Vindevogel S, De Maeyer J, Reynaert D, Engelen AM, Nuwaha F, Rubaihayo J, Bilsen J. Challenges and support for quality of life of youths living with HIV/AIDS in schools and larger community in East Africa: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019 Feb 26;8(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-0980-1. PMID: 30808419; PMCID: PMC6390353.

- Heale R, Twycross A. Validity and reliability in quantitative studies. Evid Based Nurs. 2015 Jul;18(3):66-7. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102129. Epub 2015 May 15. PMID: 25979629.